Sunny Balasubramanian

Current quantitative researcher in the crypto & equities space. Formerly at Citadel, AQR, Columbia SEAS '16. Always cracking away at new (sometimes whimsical) problems using different kinds of technology. Please reach out to me at sunny.m.bala@gmail.com if you'd like to chat about any of my prior work or would like to hack on something together. LinkedIn | GitHub

Detecting Fake Videos with Python

by

Someone on the internet uploaded a video where he slapped himself for 24 hours. Did he actually do it? TLDR; No.

I was scrolling through YouTube the other day and saw a video that was going viral. In it, a guy claimed he was going to slap himself in the face for 24 hours. The video was a full 24 hours. I skipped around through the video and, sure enough, it was just him slapping himself. Lots of the comments claimed that the video was fake. I thought so too, but I wanted to know for sure.

The Plan

Write a program to detect if there are any loops in the video. I hadn’t done any video processing with Python before so it seemed like it could be a neat.

First Attempt

Watching a video is like watching a really fast flipbook of pictures. Conveniently, that’s also what it looks like when reading the data of the video using python. Each “picture” that we see is one frame of the video. When this particular video plays, it’s playing in 30 frames per second.

In data, each frame is a giant array. This array tells us the color of each pixel at every location by specifying the amount of red/green/blue to mix (RGB). We want to see if any frames appear more than once in the video – one way to do that would be just counting the number of times we see each frame.

I did that counting using two dictionaries. One keeps track of any frames I’ve seen already. The other keeps track of groups of frames that are all exactly the same. As I go through the frames one by one, I first check if I’ve seen the image before. If I haven’t, I’ll add it to my dictionary of frames I’ve seen (seen_frames below). If I have seen that frame before, I’ll add it to the other dictionary (dup_frames) in a list along with all the other frames that are exactly like it.

(More info on the code: typically, when doing a counter like this or using the collections.counter object, you’ll be hashing the values that you’re counting under the hood. Unfortunately, the video frame arrays are not hashable – to get around this, I converted the arrays to strings before hashing and it worked like a charm.)

Code:

def find_duplicates():

# load in the video file

filename = 'video.mp4'

vid = imageio.get_reader(filename, 'ffmpeg')

all_frames = vid.get_length()

# we'll store the info on repeated frames here

seen_frames = {}

dup_frames = {}

for x in range(all_frames):

# get frame x

frame = vid.get_data(x)

# hash our frame

hashed = hash(frame.tostring())

if seen_frames.get( hashed, None):

# if we've seen this frame before, add it to the

# list of frames that all have the same

# hashed value in dup_frames

dup_frames[hashed].append(x)

else:

# if it's the first time seeing a frame,

# put it in seen_frames

seen_frames[hashed] = x

dup_frames[hashed] = [x]

# return a list of lists of duplicate frames

return [dup_frames[x] for x in dup_frames if len(dup_frames[x]) > 1]Running this code took about an hour on my macbook pro. Let’s take a look at the results:

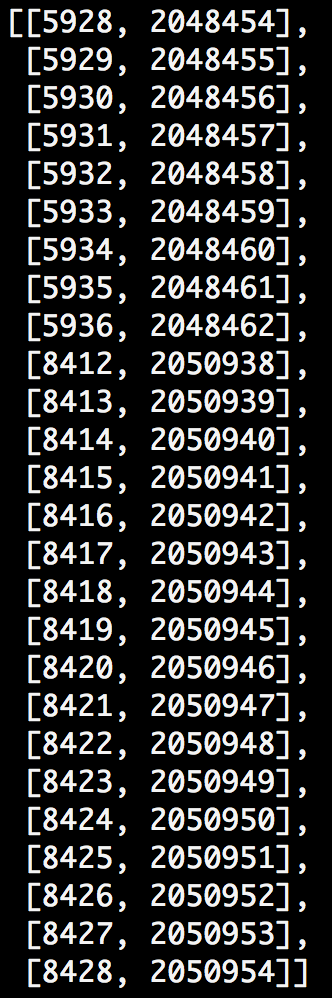

Okay, neat. So according to this, frame 5928 is the same as frame 2048454, frame 5936 is the same as 2048462, and so on. Let’s visually confirm.

Perfect. So the video is definitely fake. However, the number of matches seems super sus – it’s really low. Is it really the case that there’s only ~ 25 identical frames? That’s hardly 1 second out of the full 24 hour video. Let’s take a closer look!

The Plot Thickens

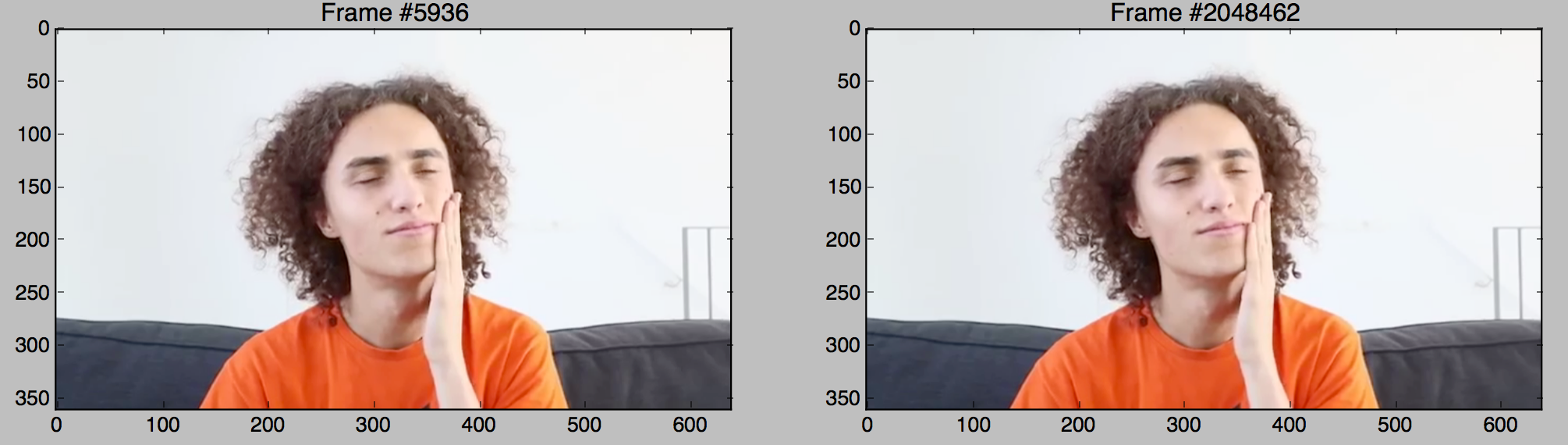

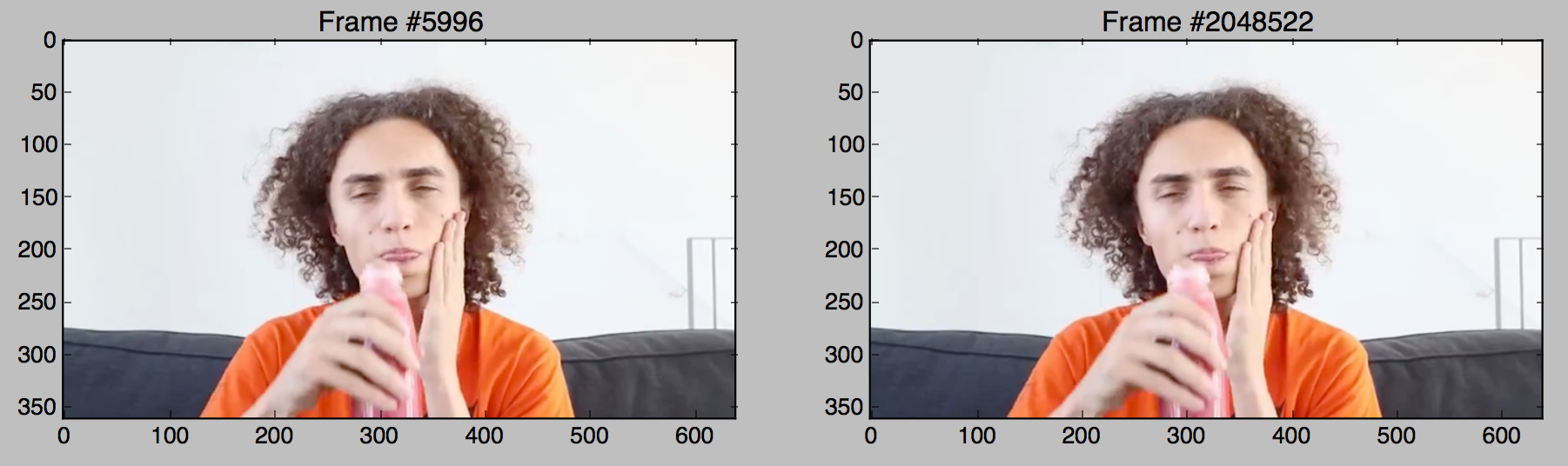

The program worked the way it was supposed to – it identified identical frames and let me know that the video was looping. Let’s check what the frames look like 2 seconds after the two images above (frame 5936 + 60 and frame 2048462 + 60).

Wait … these look identical! And yet they didn’t flag as a match?! We can subtract these two frames from each other to figure out what’s different. The subtraction works pixel by pixel on the red/green/blue values.

Great, we’ve made some cool glitch art! What actually appears to be happening is that these are just a bunch of differences in the frame coming from the fact that the video is compressed. Because of the compression, two frames that originally were identical might get a little distorted by this noise and will no longer be numerically the same (though they are visually).

Above, when I stored the data in dictionaries, I hashed each image. The hash function will turn an image (an array) into an integer. If two images are exactly the same, the hash function will give us the same integer. If the two images are different, we’ll get a different integer. The behavior we actually want is that that if two images are only slightly different we’ll get the same exact integer.

Compressing Our Compression Problems

There’s a few different kinds of hashing that each have special use cases. What we’ll be looking at here is perceptual hashing. Unlike other kinds of hashing, inputs that are close together will come out of the hash being identical. A similar approach is apparently used by reverse image searching websites, which just crawl the web and hash images they come across. Since a given picture exists at ton of resolutions and croppings all over the internet, it’s computationally convenient to check for other things that have the same hash.

However, for us there’s some new wrinkles because we aren’t exactly dealing with images, but instead a series of images each one being 1/30th of a second apart. This means that our hash function needs to be:

- relaxed enough that two frames differing only by compression noise hash to the same number

- sensitive enough that a frame and the one right before it hash to different numbers

This might be tricky.

Hashing Out aHash Parameter Selection

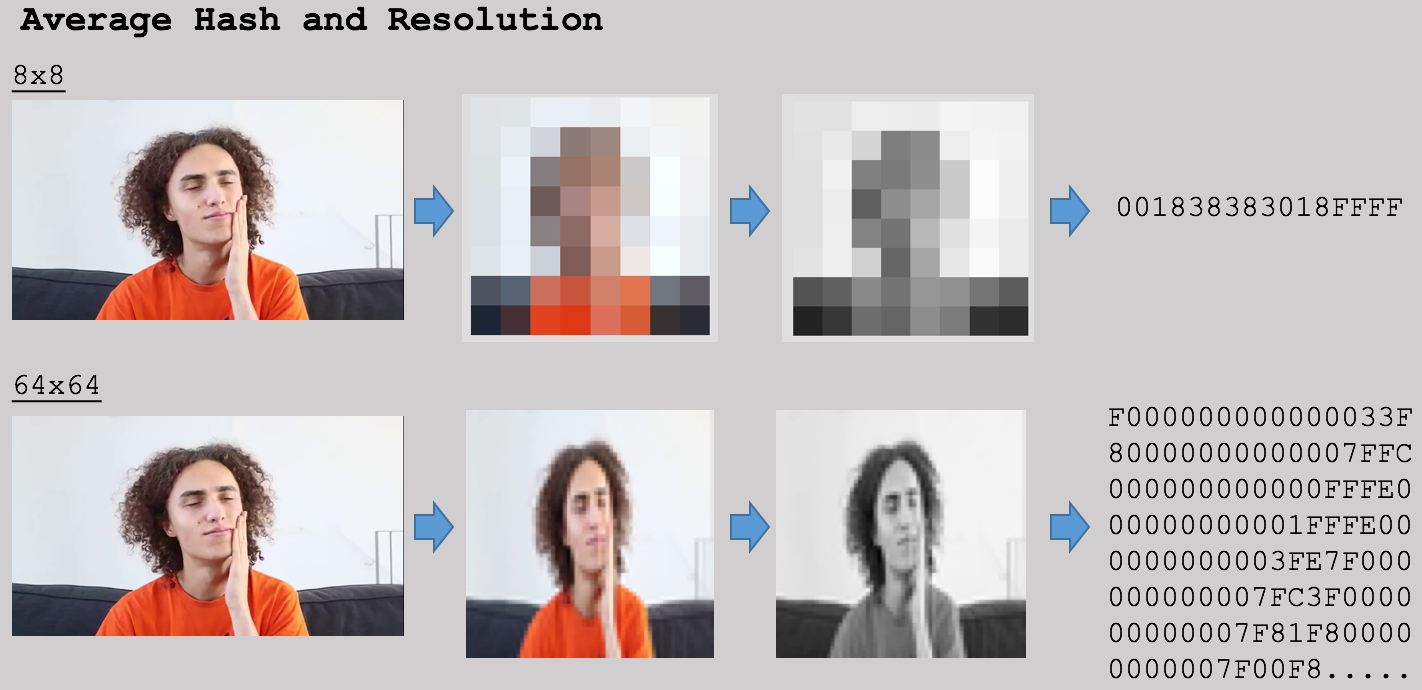

The specific hashing algorithm I’m going to try using is called average hash (aHash). There’s more information available online , but the general process is that it reduces the image resolution, turns it to grayscale, and then hashes it. By reducing the resolution, we can potentially remove the effects of the noise. However, we run the risk that adjacent frames get flagged as duplicates because of how similar they look to each other. One way that can play around with this trade-off by adjusting the resolution.

Below, I show the results of the ahash process at 8x8 and 64x64 resolution. The 8x8 looks like it downsamples too much – we lose so much information that it seems like most of the images will look the same at 8x8. At 64x64, it looks not so different than the original - it’s possible that it may not be different enough to overcome the compression noise.

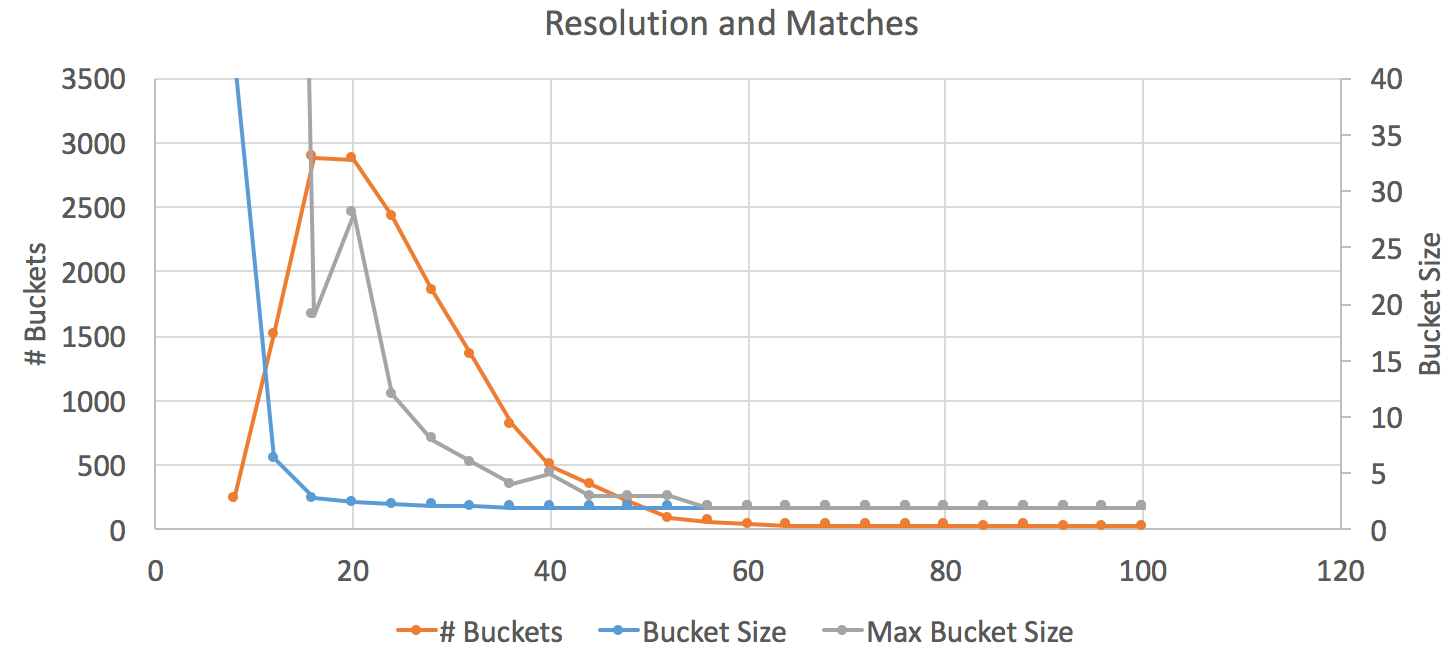

To get an idea of what resolution fits our situation best, I tried finding matches over a range of resolutions for two sections of the video that were similar. The matches returned come in the following output:

- [8,108]

- [9,109]

- [10,11,110,111]

The interpretation of the above are that frames 8 and 108 are the same as each other. Frames 9 and 109 are the same as each other but different than 8/108. Frames 10,11,110, and 111 are different from all other frames but the same as each other. This will happen because the algorithm isn’t perfect – occasionally it’ll get confused and think that two adjacent frames are identical. To track the trade offs, we can look at a few metrics:

- How many buckets of matches are there? Above, there are 3.

- What is the average number of frames in each bucket? That average is (2+2+4)/3 = 2.7.

- What is the most frames in any bucket? 4

The goal here is to get a high number of buckets (the first metric) with a low number of items per bucket (average or worst case). Theoretically, since the sections of the video I was looking at had 1 loop, there should only be 2 frames per bucket.

Okay, looks like 64 was too extreme – we barely have any buckets at the point. On the other hand, there’s an explosion in the bucket side towards the left side of the graph where all frames are detected as duplicates. The sweet spot seems to be around the peak of # buckets at 20 or so. It seems like there’s something weird about the data point at 20 frames based on the max bucket size line. There’s only so much I’m willing to do to disprove an internet video, so let’s go with 24 for the resolution of the hash.

Results

I replaced the hash function in the original one with a call to this new ahash function and re-ran the analysis. Lo and behold, tons of matches! There’s too many to display here, but I’ll show a few that are in the same bucket:

- 4262

- 72096

- 124855

- 132392

- 147466

- 162540

- 170077

- 185151

- 207762

- 252984

- etc…

These are our duplicate frames. Converting those to rough timestamps (in seconds) of when they occured,

Bingo!

In fact, by pure luck these duplicate frames happen right after he cuts the loops together. If you check out these duplicated locations, you can actually see the cut happen. It happens right in the middle of a slap! Now it’s not necessarily guaranteed that I got every match, but this is far more exhaustive than what we had before and I’m willing to call this one good enough.

I don’t follow this youtuber so I’m not sure if the video is an inside joke or anything – it was posted on April 1st – but this has definitely been a fun project to work out.